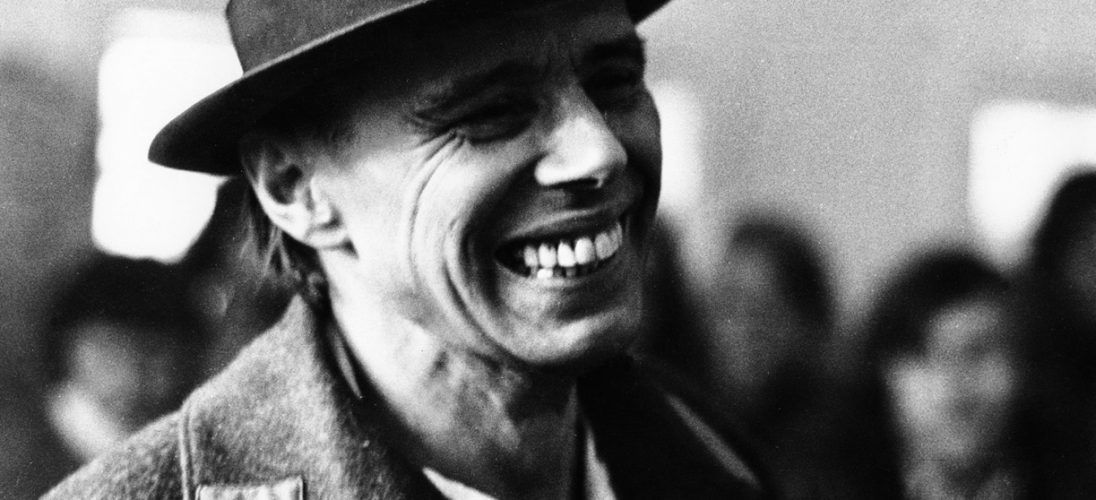

About Joseph Beuys

Enquire / Make an OfferJoseph Beuys was a German-born artist active in Europe and the United States from the 1950s through the early 1980s, who came to be loosely associated with that era’s international, proto-Conceptual art movement, Fluxus. Beuys’s diverse body of work ranges from traditional media of drawing, painting, and sculpture, to process-oriented, or time-based “action” art, the performance of which suggested how art may exercise a healing effect (on both the artist and the audience) when it takes up psychological, social, and/or political subjects. Beuys is especially famous for works incorporating animal fat and felt, two common materials – one organic, the other fabricated, or industrial – that had profound personal meaning to the artist. They were also recurring motifs in works suggesting that art, common materials, and one’s “everyday life” were ultimately inseparable.

Key Ideas

Childhood

Joseph Beuys was born in 1921 in Krefeld, a small city in northwest Germany. He was an only child, to the merchant Josef Jakob Beuys and his wife Johanna Maria Margarete Hulsermann. The two were a devout Catholic couple of the northern Rhine-Westphalian middle-class. Just months after Beuys’s birth, the family moved south to the industrial town of Kleve. Beuys would later recall, in an unsubstantiated account, that when, in 1933, the recently formed National Socialist German Workers’ Party (or Nazi Party) staged a book-burning rally at Kleve (Beuys would have been aged 12), he rescued from the flames Carolus Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (1735) – one of history’s most groundbreaking works of scientific literature. (In an ironic turn, Beuys was himself compelled by legal fiat to join the Hitler Youth movement by the time he was a teenager).

During Beuys’s early education at Kleve, his primary- and secondary-school instructors identified his predilection for drawing and music. In addition to the arts, the young Beuys also demonstrated an aptitude in history, mythology, and the social and natural sciences. Although he finally opted for a career in medicine, Beuys’s ambition proved short-lived when, in 1941, he voluntarily enrolled himself in the German air force, or Luftwaffe (allegedly to avoid the draft).

Early Training

While Beuys’s military subscription was voluntary, he had no desire to see actual combat. Thus in keeping with his interest in medicine, Beuys continued his studies in biology and zoology in the early 1940s. According to his own account of 1979, a pivotal (and, once again, unverifiable) event changed the course of Beuys’s life in March of 1944, when his battle plane was shot down over the Crimean Front in the Ukraine. Beuys claims to have been promptly rescued by a nomadic tribe of Tartars, who apparently saved his life by greasing his bruised and battle-weary body with animal fat, before wrapping him entirely – so as to raise his temperature – in felt. The importance of ancient healing aids – in this case, fat and felt – for enriching and sustaining the human mind, body, and spirit, would come to play an important and highly visible role in much of Beuys’s subsequent work as an artist.

It is notable that several eyewitness accounts are on record as contradicting Beuys’s romantic and exotic parables; in addition, there were reportedly no Tartar tribesmen occupying the region of Beuys’s alleged military plane crash. In any event, a mixture of fact and fiction would come to play a central role in Beuys’s later art works. Indeed, Beuys’s tale of heroic rescue by Tartars (whether or not true) served as something of a lynchpin for his decision, in the immediate wake of World War II, to devote himself thereafter to art and avant-garde culture.

On resuming his civilian life in 1946, Beuys enrolled in the monumental sculpture program of the Staatliche Kunstakademie Dusseldorf. Beuys responded well to the instruction of Ewald Matare, at that time a widely popular German painter and sculptor, whose work had once been proclaimed “degenerate” by the Nazis. After several years of distinguishing himself in this intimate class, Beuys was admitted, in 1951, to the more select master sculpture class of Matare (Beuys finally graduated two years later).

During his latter studies with Matare, Beuys shared a studio with Erwin Heerich, who would subsequently be celebrated as one of Germany’s most important twentieth century sculptors. Beuys’s major influences during these early years, however, were generally more remote, such as the work of Italian Renaissance painters; the scientific theories of Galileo; the writings of James Joyce; the writings of the German romantics – namely Goethe, Novalis, and Schiller – and the work of various others who Beuys admired for their generally mystical and universal qualities.

The 1950s would prove on the whole a difficult time for Beuys, in regard to both his personal life and his work. Haunted by wartime memories and constantly suffering financial hardship, he devoted the majority of his time to drawing – ultimately creating several thousand works over the course of the decade. Beuys was in pursuit of a new artistic language, one that might emerge from intense solitude and introspection. In keeping with this ambition, he restricted himself to three motifs: animals, the female figure, and landscape. Complementing this creative asceticism, Beuys turned his back on all media other than pencil, ink, and oil pigments. One example of the kind of work that emerged from this intense discipline was Woman/Animal Skull (1956-57), a highly personal, experimental and arguably mystical abstraction.

By the early 1960s, Beuys was at work on a series of drawings based on James Joyce’s epic novel, Ulysses (1918-22). This project was conceived as an extension of the novel itself; indeed, according to Beuys, he created the drawings at Joyce’s own request (i.e. as though by way of telepathy, as Joyce had died in 1941). The claim that a literary ghost could act as his personal muse is indicative of Beuys’s fascination with a creative process issuing from somewhere between fact and fiction, and physical and metaphysical self constituency, with the result that the simplest gesture might ultimately bear the status of a profound artistic statement.

Mature Period

Thus following on the heels of a tumultuous early life, Beuys’s first official validation arrived in 1961, when he was appointed Professor of Monumental Sculpture at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Dusseldorf (where he himself had earlier studied). Beuys made significant waves while occupying this post, first by abolishing all entry requirements (virtually anyone could join his classes), and associating with a group of experimental creatives at Dusseldorf, among them progressive video artist Nam June Paik, as well as others closely affiliated with the recently formed Fluxus Group.

These new associations would act as a direct influence on Beuys’s first ventures in the realm of performance art, the resultant works of which have come to epitomize Beuys’s aesthetic sensibility in the popular mind. Fluxus stressed the importance of applying oneself to an unusually broad range of media, including painting, drawing, performance, sound art, sculpture, video, collage and poetry. In Beuys’s case, his artistic practice covered four major areas: so-called traditional art (painting, drawing, sculpture installation); art performance; art theory and academic teaching; and political activism.

In 1964, while Beuys was in the middle of performing a work at the Technical College Aachen, a student suddenly punched him in the face, bloodying the artist and causing the event to come to an abrupt conclusion. The work would continue to resonate, however, when a photograph of Beuys, nose bloodied and arm raised like that of a prize fighter, began to circulate. Beuys seized the opportunity, creating a heroic account of his life in the form of a fictional curriculum vitae, thus effectively transforming the utterly quotidian turn of events into a newly fashioned, near-legendary persona.

Beuys held his first solo performance one year later at the Galerie Schmela, in Dresden. How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare opened on November 26, 1965, and ever since, countless Beuys enthusiasts have come to regard this particular work his signature performance piece. Like a morbid soothsayer, Beuys sat himself in a store window, clad in felt and cast iron foot piece; while cradling a furry rabbit carcass, he carried out, with metronomic precision, a series of ritualistic, abstruse gestures, as though the fate of the world hinged on the mysterious rhythms of this scrappy pulpit. The work cinched what had been, up to that time, a growing fascination with Beuys by the international art world and public alike.

Other non-art, or found material that Beuys used in much of his sculpture and conceptual art was animal fat. Beuys used this organic material in both its liquid and solid states, the implicit potential for continual metamorphosis of the fat suggesting a great spiritual substance. By constructing art from something that was, fundamentally in and of itself, a life-sustaining material, Beuys spoke to people on both physically and psychologically visceral levels. This is evident in seminal works such as Fat Corners (1960) and Fat Chair(1964).

Much as Beuys had worked single-mindedly with drawing in the 1950s, he likewise steadily concentrated on manipulating felt throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, using it alternately as sculptural medium, sound insulator, and poetic metaphor. Works that epitomize this varied practice include Homogenous Infiltration for Grand Piano (1966), Homogenous Infiltration for Cello (1967), The Pack (1969), and Felt Suit (1970) – the latter work notably lacking Beuys’s typically elaborate and/or metaphorical titles. Felt Suit was simply a quasi-cosmic turn of haberdashery, a simple men’s suit tailored carefully after one of the artist’s own. On having donned the suit for a 1970 performance, Beuys subsequently claimed that it symbolized “protection of the individual from the world,” no less the fundamental isolation of the human condition.

Never the docile academic or administrator, Beuys was eventually dismissed from his professorship at the Kunstakademie (1972), indeed owing partly to his unorthodox practice of accepting anyone into his classroom. It was never that Beuys believed virtually anyone could qualify as an artist merely by attending art school; rather, Beuys simply maintained that anyone who wished to attend art school should have the right to do so, regardless of natural talent.

Beuys’s art performances grew ever more elaborate throughout the 1970s. While continuing to utilize his already standard wares of felt, animals, and organic materials, he supplemented them with new elements in order to suggest new symbolic meanings, no less to infuse his own particular brand of “Conceptual art” with a new visual syntax. For his 1974 performance I Like America and America Likes Me, Beuys traveled to New York City for a three-day stint at the Rene Block Gallery. Beuys sequestered himself in the space, having filled it earlier with various objects, such as straw, a triangle, a felt blanket (in which he would wrap himself) and a wild coyote. An extension of this conceptual montage into the everyday world was suggested in the artist’s insistence on traveling to and from the gallery daily in a curtained ambulance, and his being conveyed by stretcher between the ambulance and the gallery (or his temporary residence) so that he would neither set foot on American soil nor ever directly lay eyes on the city.

Later Years and Death

Late in life, Beuys founded many political organizations – especially following his 1972 dismissal from his professorship – such as the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research (1974), and the German Green Party (1980). Beuys’s art itself also gradually became more political, all the while continuing to be informed by his concept of “Social Sculpture,” according to which the implicit message of any of his labors was that society itself was to be understood as the real “art work.” This all-inclusive and contentious ideal is perhaps best reflected in the artist’s 7000 Oaks (1982-87), a work of land art, urbanization and environmentalism all in one.

Following a long illness, Beuys succumbed to heart failure on January 23, 1986 in Dusseldorf, not far from his place of birth. The trees of 7000 Oaks continued to be planted by others after Beuys’s death, thus implying the artist’s continued presence well after his own soma had assumed a place in the realm of the invisible. Beuys remains, to this day, one of the few artists whose life and work continually spark debate and a sense of mystery over what constitutes art’s legitimate province, and what might constitute the true limits of human expression.

Legacy

Beuys’s insistence on the fundamentally democratic nature of human creativity suggested that every fully thinking and feeling person is, by definition, an artist, has left a widely influential and creative legacy since his death in 1986. While Beuys had always made an impact on his fellow Fluxus colleagues since the early 1960s, he would ultimately come to play a larger role in lending credence to the notion, increasingly popular since the mid 1990s, that art should address social, political, and related concerns by blurring the boundaries between its own practice, as a professional discipline, and everyday reality. This meeting of the studio and the street, as it were, leads from Fluxus happenings to the ecological art of the more recent past, as well as a current generation’s fascination for elements of chance, random encounter between an artist and her/his audience, the participation of the audience in the art work’s completion over time, the incorporation of everyday materials within interactive installations and happenings, and so forth – indeed much of what has come to fall under the rubric, since the late 1990s, as “Relational Aesthetics” (see the book of the same name by French curator and art theorist Nicolas Bourriaud). Beuys has also made a lasting impact on environmental art, such as in the case of Robert Smithson, from the 1960s to the present.

Although the Fluxus movement of the 1960s was not formally founded by Beuys, it owes in large part its lasting legacy to his widely acknowledged practice and example. This is particularly the case in regard to Beuys’s aesthetic of Social Sculpture, which suggested art’s potential to transform the life of the individual observer, as well as the social condition of her/his larger culture. Beuys believed that if one were, by default, an artist, then one might be an artist everywhere, or in every context in which one finds oneself – the art studio proper, the classroom, and the “street” offering equally advantageous circumstances for creative experience.

To view works in our gallery by Joseph Beuys please click here:

For the latest updates please click follow us on our Instagram page here:

Are you interested in something? Do you have a question?

Send us an email below and we'll be in touch very soon.

[forminator_form id="6109"]