About Alistair Park

Enquire / Make an OfferTo learn more about Alistair Park please read this excellent article by Dr. Ian Massey from July 2015.

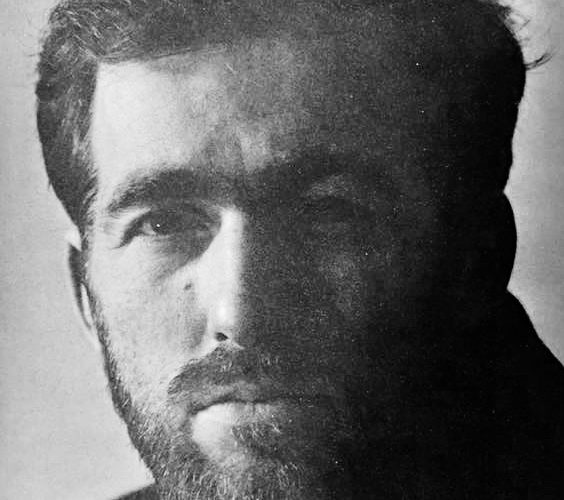

Alistair Park (1930–1984)

Female Nude was my introduction to the artist’s work, and I felt compelled to find out more. His son Stephen, also an artist, kindly responded to emails and forwarded material that he and his brother and sister, along with their late mother, had put together as a record of his father’s life. Born in 1930, Park grew up in Kirkcaldy, and studied at Edinburgh College of Art from 1947. Like many artists, his main income was from teaching, and he later taught at the college, then subsequently at Ainslie Park High School in Edinburgh, Bradford College of Art, and at Newcastle Polytechnic from 1969 until his death.

Park’s early aptitude is evident in two pictures made whilst a student; the rather academic life class painting Seated Female Nude (1951), and the more stylised Two Figures on Street Corners (1952). Later, the vivid hues and formal delineation of Yachting Lake (1957) show him immersed in the expressionism of Edvard Munch and Emil Nolde. The intense colour of this painting is comparatively rare in the artist’s work, with its overall predominance of earth and flesh tones, blacks and deep reds.

Whilst two densely worked nudes from 1961 are characteristically similar to the Female Nude of 1959, the formal language of Park’s work of the sixties became generally more abstract and allusive. Paint tended often to be more dilute, with looser brushwork and a more evident use of linear drawing. At the same time, the work’s meanings were heartfelt and personal, for as Stephen Park has described: ‘I don’t think Alistair was prone to literal interpretation but he liked to invest things with a sense of significance, I think he would have called his pictures “totems” or something like that.’ With their faux naïve graffiti-like drawing, Little Man (1961) and Blue Little Man (1962) very probably refer to the artist’s two sons, born in the years the paintings were made; whereas A Little Woman (1962) reads as a painting about maternity, the artist’s wife Sara rendered as a group of glowing orange-ochre shapes, her baby as a figure-of-eight.

During the fifties and early sixties Park exhibited regularly in group shows in Edinburgh, Newcastle and York, and a show of Scottish painters in Toronto in 1961. He held a solo exhibition at The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh in 1962, and later that year showed alongside Paul Huxley at The Rowan Gallery, London, where he subsequently had a solo show in 1965. The latter included Flags and Banners (1964), from a series of works inspired by the Kennedy assassination. Though it initially appears abstract, the composition shows the presidential limousine viewed from overhead, set amongst the fluttering flags and banners of the cavalcade. The Kennedys are represented merely as simple oval head shapes; that of the president smeared in a bloody alizarin. It is an urgent, angry painting, reflecting the widespread shock and confusion following this symbolic event. The small acrylic painting Some Foreign Flag (1965) with its collage-like battle-torn remnant, hints also at violence, its title perhaps a play on ‘some foreign field’.

Park’s London shows were neither critically nor commercially successful, and his morale declined.† He abandoned painting in the seventies, believing that, in an era of conceptualism, painting was dead. Towards the end of that decade a hemorrhage resulted in the loss of vision in one eye, and aggravated a longstanding depressive tendency. Bouts of difficult behaviour exacerbated by increased alcohol consumption made him progressively harder to live with, and eventually his wife left him. Though he later returned to painting, showing with Richard Demarco’s Edinburgh gallery in the early eighties, Alistair Park died following a heart failure at the age of fifty-four in August 1984.

Dr Ian Massey, writer and curator – www.ianmasseyart.co.uk

* Unfortunately, Park’s Female Nude of 1959 has not yet been catalogued by Art UK and so isn’t illustrated here. To see the work, readers may enquire with National Galleries of Scotland

† Although Park may have felt that his exhibitions were overlooked, in 1963 the artist and critic T. Elder Dickson noted of him: ‘Park, a meditative and resourceful painter, presented a successful exhibition in London last year.’ (T. Dickson Elder, Scottish Painting – the modern spirit, Studio International, December 1963, p.243)

To view works by Alistair Park in our gallery please click here:

For the latest updates please click follow us on our Instagram page here:

Are you interested in something? Do you have a question?

Send us an email below and we'll be in touch very soon.

[forminator_form id="6109"]